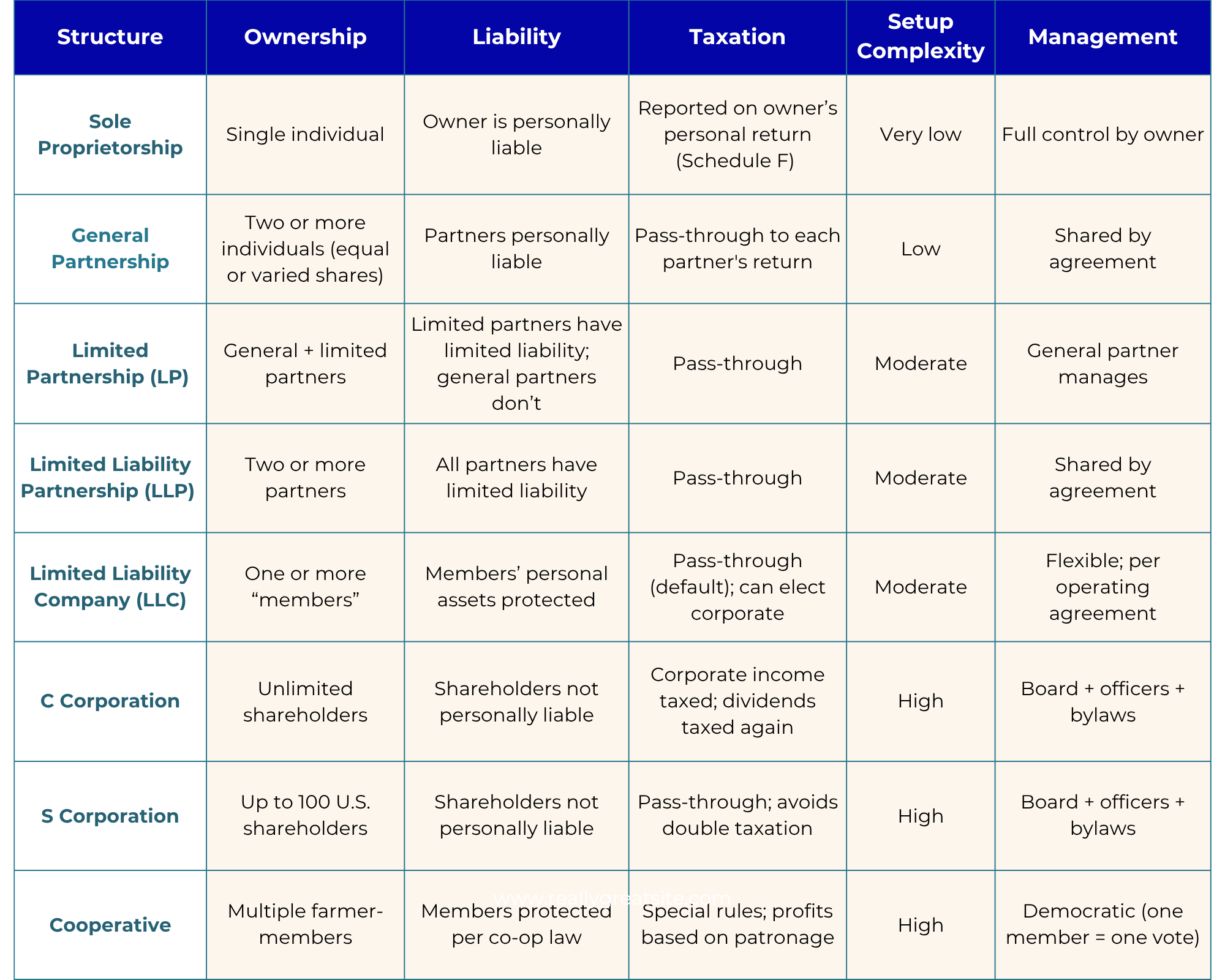

When starting or expanding a farm business, one of the most important early decisions you'll face is selecting the right business structure. This decision will influence how your operation is taxed, how liability is handled, how ownership is transferred, and how daily decisions are made. If you're considering incorporation, start by reviewing our Guide to Incorporating Your Small Business.

In agriculture, business structures aren’t just a legal formality — they impact land ownership, business transition, and the ability to grow or diversify your enterprise. Below is a breakdown of the most commonly used business structures and what each entails.

Sole Proprietorship

A sole proprietorship is the simplest business structure. It exists when one individual owns and operates the business without formally registering with the Secretary of State as a different entity type.

Key Features:

The farm and the owner are legally the same entity.

The owner reports farm income and expenses on their personal income tax return (typically using IRS Schedule F).

There is no formal registration required beyond local permits or a business license (if needed).

The owner has full control over all decisions and receives all profits directly.

Because there is no legal separation, the owner is personally responsible for all business debts and obligations.

Use in Agriculture:

Sole proprietorships are common among small, single-owner farms, part-time farming operations, or when testing a new business concept before scaling up.

General and Limited Partnerships

A partnership is formed when two or more people agree to run a business together. In agriculture, this often takes the form of a family-run farm or two parties pooling resources to manage land and livestock.

Key Features:

General Partnership (GP):

All partners share in management responsibilities and liabilities.

Each partner is personally responsible for the debts of the business.

Profits are divided according to the partnership agreement and reported on each partner’s individual tax returns.

Limited Partnership (LP):

Includes at least one general partner who manages the business and assumes liability.

Limited partners contribute capital and share in profits but do not participate in day-to-day management.

Liability of limited partners is typically limited to their investment in the business.

Limited Liability Partnership (LLP):

All partners have limited liability.

Partners may share management duties while maintaining protection from each other’s liabilities (useful in professional services but less common in agriculture).

Use in Agriculture:

Partnerships are often used in multi-generational family farms or collaborations between landowners and operators, where each party contributes labor, land, equipment, or capital.

Limited Liability Company (LLC)

An LLC is one of the most popular structures in modern agriculture, providing legal protection to owners while allowing for flexible management and tax treatment.

Key Features:

Owners are called “members.” An LLC can have one member (single-member LLC) or multiple members (multi-member LLC).

The LLC exists as a separate legal entity from its members, offering liability protection.

It does not pay federal income taxes as an entity by default. Instead, profits and losses are passed through to the members’ individual tax returns unless the LLC elects to be taxed as a corporation.

The operating agreement defines each member’s role, ownership share, and management duties.

The LLC can own land, equipment, and other assets in its name, which is useful for structuring multi-owner land holdings or diversified farm activities.

Use in Agriculture:

LLCs are common in farming operations that involve multiple family members, outside investors, or value-added enterprises such as farm stores, agritourism, or product processing. They are also helpful in separating personal and farm assets.

Corporations (C Corporation and S Corporation)

A corporation is a legally distinct entity that is owned by shareholders and governed by a board of directors. In farming, corporations are often used for complex or high-value operations, especially those needing a formal structure for growth, investment, or succession.

C Corporation

Key Features:

The corporation pays taxes on its profits directly. If profits are distributed as dividends to shareholders, those are taxed again on the individual level.

Shareholders are not personally liable for the debts or liabilities of the corporation.

Requires articles of incorporation, corporate bylaws, shareholder meetings, and formal recordkeeping.

Ownership is represented by shares of stock, which can be sold or transferred.

S Corporation

Key Features:

Must meet IRS requirements, including a limit of 100 shareholders who must be U.S. citizens or residents.

Income and losses are passed through to shareholders and reported on their personal tax returns (avoiding double taxation).

Maintains the same liability protections and corporate governance rules as a C corporation.

Use in Agriculture:

Corporations are useful for larger agricultural businesses, farms with non-family investors, or multi-generational operations that want clear ownership rules and a process for stock transfer. They also provide a clear structure for managing payroll, benefits, and staff. S corporations are more common in agriculture than C corporations; they’re often used by small businesses and medium to large farming operations

Agricultural Cooperative (Co-op)

A cooperative is a member-owned business formed to meet shared economic, social, or cultural needs. In agriculture, co-ops are widely used for marketing products, buying supplies, or accessing shared equipment and infrastructure.

Key Features:

Members contribute equity and collectively own the business.

Each member typically has one vote, regardless of the size of their investment or farm.

Profits are returned to members based on their level of use or "patronage" of the co-op, not on capital contributions.

Co-ops can be formed to sell products (marketing co-op), purchase supplies (supply co-op), or provide services like grain storage, insurance, or equipment access.

Use in Agriculture:

Co-ops are common among small and mid-size farms that want to increase bargaining power, reduce input costs, or expand market access through collective efforts. Co-ops can be a good option for a group with a common goal if everyone understands that they will share control of the business.

Conclusion: Aligning Structure with Your Farm’s Needs

Each farm is unique. A small organic produce grower might thrive as a sole proprietorship, while a large ranch with multiple family owners might need the formality and protections of an LLC or corporation. As your farm grows — and as goals like business transition, investment, or diversification come into play — your structure may need to evolve.

Before choosing or changing your structure, consider:

Who owns the land, and who operates the business?

What risks do you face (e.g., liability, weather, equipment damage)?

What’s your long-term plan: succession, scaling, or selling?

How complex are your finances, staff needs, and revenue streams?

Meeting with an attorney or accountant who understands agricultural law and tax rules can help you make the best decision based on your goals, not just your current size. You can also use Kentucky’s Secretary of State website for annual filings and other online resources.

To understand your options, you can also contact KCARD at (859) 550-3972 or kcard@kcard.info.